Hello my very goo friends! This week was EPIC, I done so much to expand my reach, make it easy to navigate my Inn and really worked hard on various Homebrew creations, despite all the heat outside. If you have missed the Elven Maid Inn now have a Link-Tree, a small website to navigate you between my social media by going to https://beacons.ai/elvenmaidinn you will see links to my other spaces like Instagram, Ko-Fi, Youbute or you will find all items that I have for sell include Tales from The Tavern Magazine as well as Displate Posters and EMI Classic Gaming T-shirts.

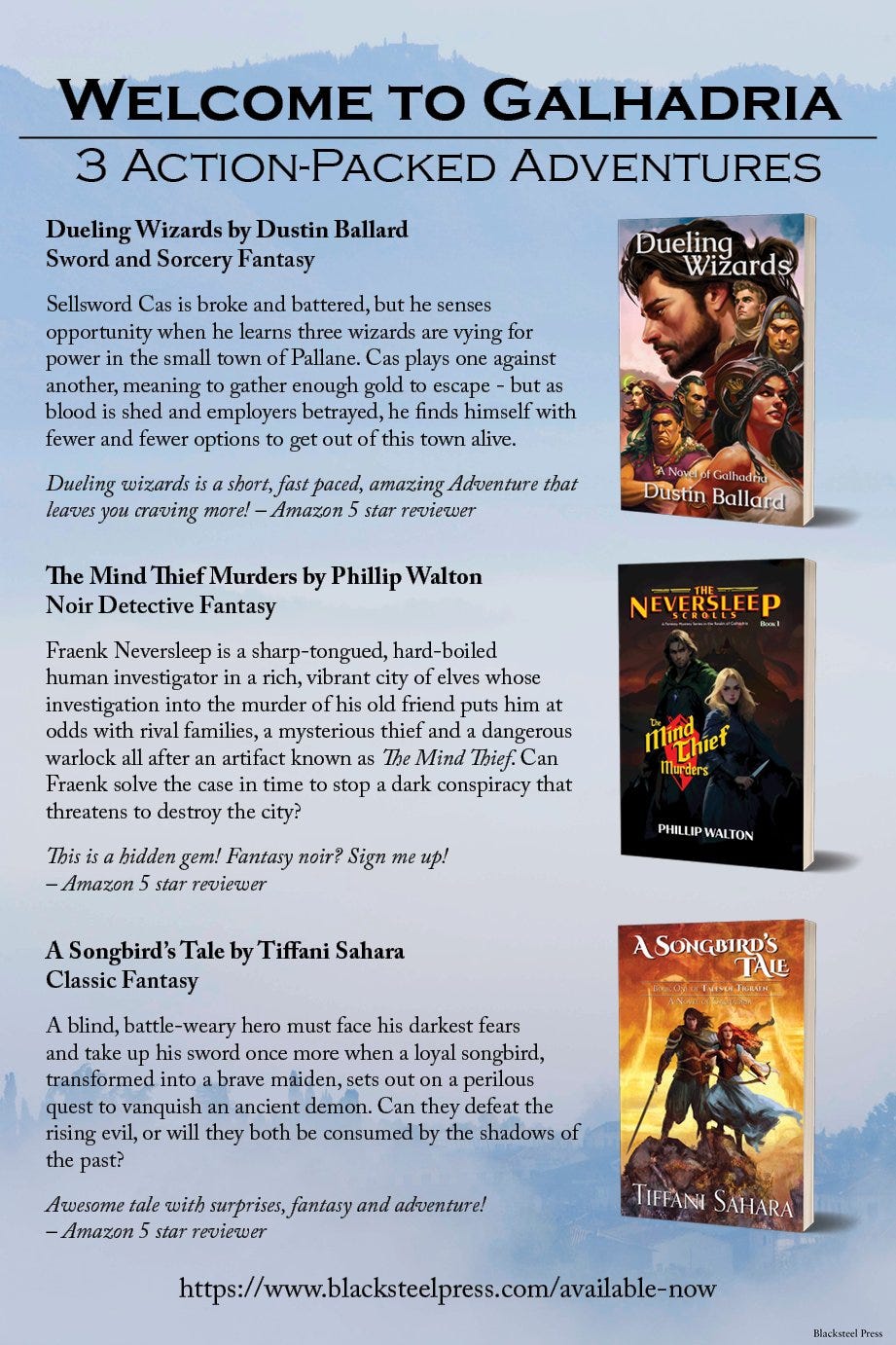

Lastly let me thank to Dustin Ballard a man who sponsoring my blog articles since February. Sometimes I feel like not having energy or motivation to write, It makes me really bad, but I know Dustin is waiting for me to fulfil my obligation and deliver article that he supported, many articles were created not because I feel like it, but because I had this obligation to write it, and as soon as I started writing first paragraph the magic happened. So Thank You Dustin! For pushing my lazy ass to work, because without this support I would play Yakuza game right now instead of doing what I really love, creating. The first step is always the hardest, that is true if you don’t have someone that push you to move forward. Help me thank Dustin by checking his book Dueling Wizards: The Sellsword Saga, available now on Amazon!

Thank you for enduring all those updates from EMI. But I am super proud of work I done this week, there is another thing that is happening or already happened my X account just reached 5k followers. To celebrate this I had brainstorming on Discord with my community on Discord and we were thinking an event that could be done as part of celebration. One of my friends came up with idea of a Calendar that made me think.

Why we are using Earth Calendar in our unique homebrew worlds and if we make one, how we make sure that it has sense. To answer this question we will need to take our Real Life Calendar and dismantle it, see why we have seven days in a week, why we have 12 months in a year and why we have specific amounts of days per month. By knowing that we will have foundation to make our own calendars in imaginary worlds.

Alright, my epic friends, let’s dive into the cosmic machinery behind our calendar and unravel why it’s built the way it is, so we can craft something truly legendary for our homebrew worlds! First, let’s tackle why a year has roughly 365 days, sometimes sneaking in that extra day to make 366. It all comes down to how long it takes our little blue planet to do a full lap around the Sun. That journey, called a solar year, clocks in at about 365.2422 days, 365 days plus a pesky 5 hours, 48 minutes, and change. Ancient folks, like the Egyptians and Babylonians, figured out that 365 days was a solid starting point for a year, but it wasn’t perfect. If you stick with just 365 days every year, your calendar starts drifting, and soon your winter festivals are happening in summer. To fix this, the Romans, under Julius Caesar, introduced the leap year. Every four years, we add an extra day, February 29, to soak up that extra fraction of a day, making the average year 365.25 days. Later, Pope Gregory XIII tweaked it further with the Gregorian calendar, skipping some leap years (like century years not divisible by 400) to keep things even tighter, averaging 365.2425 days. That’s why we’ve got 365 days most years, with that cheeky 366th day popping up to keep our seasons in line.

Now, why 12 months? This one’s got its roots in the Moon and a bit of human practicality. Way back, ancient cultures like the Babylonians were obsessed with the Moon’s cycles. The time from one new moon to the next is about 29.53 days, and if you multiply that by 12, you get roughly 354 days, pretty close to a solar year. Twelve lunar cycles felt like a natural way to chop up the year, and it was manageable for tracking seasons, planting crops, or planning rituals. The Romans ran with this idea, but their early calendar was a mess. Romulus, the legendary founder of Rome, supposedly started with a 10-month calendar totaling 304 days, leaving winter as a vague, uncounted blob. King Numa Pompilius, around 700 BCE, said, “Nah, we can do better,” and added January and February, making it a 12-month, 355-day lunisolar calendar. Why 12? It’s a super divisible number, splits nicely by 2, 3, 4, or 6, which made it handy for organizing society. When Julius Caesar overhauled things into the Julian calendar, he kept the 12 months but aligned them with the solar year, not just the Moon, to make sure the seasons stayed put. That 12-month structure stuck because it was practical, culturally ingrained, and spread like wildfire through the Roman Empire and later Christianity.

Speaking of the Moon, those lunar phases are why we think of months as tied to moons in the first place. The word “month” comes from the Old English monath, linked to mona, meaning Moon. Each month roughly mimics the Moon’s cycle: new moon to crescent, full moon to waning, and back again. In ancient times, a month was literally the time it took for the Moon to go through its phases, about 29 or 30 days. That’s why many early calendars, like the Jewish or Islamic ones, are lunar or lunisolar, with months pegged to the Moon’s rhythm. Our modern Gregorian calendar doesn’t strictly follow the Moon anymore, it’s solar-based to match the Earth’s orbit, but the 12-month setup still echoes those ancient lunar roots. For your homebrew world, you could make months match your planet’s moon cycles, maybe with two moons creating overlapping months or a single massive moon stretching phases to 40 days. The key is making it feel like your world’s people would naturally track time this way.

Now, why do some months have more days than others, and where do those names come from? Buckle up, because this is where history gets delightfully messy. The Julian calendar set the stage for our modern month lengths, but they’re a patchwork of astronomy, politics, and ego. January has 31 days and is named after Janus, the two-faced Roman god of beginnings, perfect for kicking off the year. February, with its 28 days (29 in a leap year), gets its name from Februa, a Roman purification festival, and it’s short because it was the last month added to the Roman calendar, getting the leftover days. March, also 31 days, honors Mars, the god of war, and was originally the first month in the Roman year, a time for starting military campaigns. April, 30 days, might come from aperire (Latin for “to open,” like spring buds) or Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love. May, 31 days, is likely named for Maia, a Roman goddess of growth, while June, 30 days, nods to Juno, queen of the gods.

July, with 31 days, was renamed by Julius Caesar himself, who decided his birth month (formerly Quintilius, meaning “fifth”) deserved his name after he fixed the calendar. August, also 31 days, got its name from Emperor Augustus, who didn’t want to be outdone by Caesar and reportedly stole a day from February to make his month just as long. September through December, 30, 31, 30, and 31 days, respectively, come from the Latin words for seven (septem), eight (octo), nine (novem), and ten (decem), because they were the seventh through tenth months in the old Roman 10-month calendar. The uneven lengths (28, 30, or 31 days) are a compromise to fit the 365-day solar year while keeping months roughly lunar-length. Julius Caesar’s astronomers tried to alternate 30 and 31 days, but political meddling (like Augustus’s ego) and the need to avoid bad luck (Romans disliked even-numbered days for some festivals) led to the hodgepodge we have now.

Let’s keep the fire burning and dive deeper into the cosmic gears of our calendar, now it’s time to crack open the mystery of why we have seven days in a week and how the names of the days, like Tuesday’s sneaky connection to both Mars and a Norse god, came to be. The seven-day week is one of those things that feels so natural we barely question it, but it’s got roots in ancient stargazing and mythology. Back in the day, around 700 BCE, the Babylonians were obsessed with the sky. They noticed seven things moving across the horizon: the Sun, the Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. These were the “planets” of their time, but not like we think of planets today. The word “planet” comes from the ancient Greek planētēs, meaning “wanderer” or “traveler,” because these celestial bodies seemed to roam the sky unlike the fixed stars. The Sun and Moon were counted as planets because they moved too, tracing their paths across the heavens. The Babylonians thought these seven wanderers had divine powers, influencing everything from harvests to battles, so they built a seven-day cycle, with each day ruled by one of these celestial gods. This wasn’t just astronomy, it was astrology, a way to organize time and life around the cosmos.

The seven-day week caught on because it was practical and mystical. Seven was a sacred number in many cultures, think seven wonders, seven seas, and it divided the lunar month (about 29.53 days) into roughly four parts (29.53 ÷ 4 ≈ 7.4 days). The Hebrews also had a seven-day week, tied to the creation story in Genesis, with the Sabbath as a day of rest. By the 1st century BCE, the Romans picked up the Babylonian system, naming each day after one of their gods linked to those seven “planets.” When the Roman Empire spread, so did the seven-day week, becoming the backbone of the Western calendar. It’s wild to think our week is a cosmic hand-me-down from Babylonian star-watchers, but that’s the magic of history!

Now, let’s talk about the names of the days and why they’re a mix of Norse and Roman vibes, especially why Tuesday sounds nothing like Mars but connects to a Norse god instead. The English names for the days come from a mash-up of Roman planetary gods and Germanic/Norse mythology, thanks to the Anglo-Saxons who settled in Britain. The Romans named their days after their gods, tied to the seven planets, but when the Germanic tribes (including Anglo-Saxons) adopted the system, they swapped in their own gods, who matched the Roman ones in spirit. Sunday is the Sun’s Day, from Old English Sunnandæg, straight from the Roman dies Solis (Day of the Sun). The Sun was a symbol of life and power, and both cultures kept it simple, naming the day for the celestial body itself. Monday is the Moon’s Day, from Mōnandæg, echoing the Roman dies Lunae (Day of the Moon). Again, no god needed, just the Moon’s mystical glow. Tuesday gets spicy. In English, it’s Tīwesdæg, named after Tiw (or Týr in Norse mythology), a Germanic god of war and justice. The Romans called this day dies Martis, after Mars, their god of war. Why the swap? Tiw was the Anglo-Saxon equivalent of Mars, both were fierce, battle-ready deities. The Anglo-Saxons didn’t use the Roman name because they wanted their own gods in the mix, so they picked Tiw to stand in for Mars. In Spanish, Tuesday is Martes, which keeps the Roman dies Martis (Day of Mars) intact, showing how Romance languages stuck closer to Latin roots. English, with its Germanic base, went the Norse route, which is why Tuesday sounds nothing like Mars but carries the same warlike vibe through Tiw.

Wednesday is Wōdnesdæg, named for Woden, the Anglo-Saxon version of Odin, the Norse god of wisdom, magic, and war. The Romans called it dies Mercurii, after Mercury, god of communication and trickery. Woden was a wanderer and seeker of knowledge, much like Mercury, so the Anglo-Saxons saw him as a fitting match. Thursday is Þunresdæg, or Thunder’s Day, for Thor, the Norse god of thunder and strength, swapping in for Jupiter, the Roman thunder-wielder, from dies Iovis (Day of Jupiter). Thor’s hammer, Mjölnir, made him a perfect stand-in for Jupiter’s lightning bolts. Friday is Frīgedæg, named after Frigg, a Germanic goddess of love and fertility (sometimes linked to Freyja), replacing Venus, the Roman love goddess, from dies Veneris (Day of Venus). Finally, Saturday is Sæternesdæg, the only day that kept its Roman name, from dies Saturni (Day of Saturn), god of time and agriculture. The Anglo-Saxons didn’t have a clear equivalent for Saturn, so they left it as is.

So, why did the Anglo-Saxons use Norse/Germanic gods like Tiw, Woden, Thor, and Frigg instead of Roman or Greek ones like Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, and Venus? It’s all about cultural pride and adaptation. When the seven-day week reached the Germanic tribes in the early centuries CE, they were integrating Roman ideas but wanted to honor their own mythology. The Roman Empire was a distant power, and the Anglo-Saxons, living in Britain by the 5th century, had their own gods, stories, and language rooted in Germanic and Norse traditions. Instead of borrowing Latin names wholesale, they matched their gods to the Roman ones based on shared traits: war for Mars and Tiw, thunder for Jupiter and Thor, love for Venus and Frigg. This wasn’t just a translation, it was a way to make the calendar their own, grounding it in their spiritual world. Romance languages like Spanish kept the Latin names (Martes for Mars, Miércoles for Mercury) because they evolved directly from Latin. English, built on Old English and influenced by Norse-speaking Vikings, took the Germanic path, giving us this unique blend.

Alright, we’re ready to wrap up this cosmic journey and give you the tools to craft a calendar that’ll make your homebrew world feel like a living, breathing legend! Imagine a world orbiting a binary star system, where the year is 420 days long because that’s how long it takes to loop around both suns. Instead of 12 months, you’ve got eight “seasons,” each tied to the shifting dominance of the red or gold star, with names like Emberwake or Gildfall, reflecting the sky’s colors. Each season could last 52 or 53 days, and you might have a wild, uncounted festival day at the year’s end when both stars align, a time for chaos and revelry. For weeks, ditch the seven-day vibe and go with six-day cycles, each day named after a primal element, Flame, Tide, Stone, Gale, Root, and Void, because your world’s gods forged reality from these forces. The sixth day, Voidday, could be a quiet time for reflection, when the locals avoid loud noises to keep the void from stirring. This setup roots your calendar in your world’s astronomy and mythology, making every date feel like a story.

Or picture a tidally locked planet, one side scorched, the other frozen, with a habitable twilight ring. The year might be 300 days, based on the planet’s slow wobble, divided into 10 months named after ancient heroes who tamed the twilight, Kael, Veyra, and so on. Each month could have 30 days, but every fifth month, you add a “Balance Day” to honor the equilibrium of light and dark, keeping the total at 302 days. Weeks could be four days long, tied to the four winds that sweep the twilight ring, with names like Zephyr, Howl, Whisper, and Roar. Your people might treat Howlday as a time for storytelling, when the wind carries ancestral voices. This calendar reflects the planet’s unique environment and cultural values, grounding your world’s time in its physical reality.

For a high-fantasy twist, imagine a world with three moons, each with a different cycle: 20 days, 30 days, and 40 days. Your calendar could have 12 months, but they’re staggered to align with the rare “Triple Full,” when all three moons shine full every 240 days, marking a sacred year. Months might be named after virtues, Valor, Mercy, Wit, reflecting the gods’ gifts, with 20 days each for simplicity. Weeks could be five days, named after the five senses, Sight, Sound, Touch, Taste, Smell, because your world’s mystics believe time is a sensory experience. Smellday might be when markets overflow with spices, tying the calendar to daily life. This setup lets you play with complex lunar cycles and cultural quirks, making your world feel dynamic and layered.

Another idea: a post-apocalyptic world where survivors track time by the pulses of a dying magical crystal, the Heart of the Old World. The year is 400 days, the time it takes the crystal to complete one “heartbeat.” You could have 16 months, each 25 days, named after lost cities, Ashkarn, Veltros, Lumira, to keep their memory alive. Weeks might be 10 days, each named after a tool of survival, Blade, Flint, Rope, Map, and so on, because time is about enduring. Mapday could be when wanderers share tales of safe routes, weaving the calendar into the culture of survival. This calendar feels gritty and tied to the world’s history, perfect for a harsh setting.

These are just sparks, mix and match! Start with your world’s astronomy: how many suns, moons, or stars shape its cycles? Then layer in culture: what do your people worship, fear, or celebrate? Name days, weeks, or months after gods, events, or elements, and let the calendar reflect your world’s quirks, like a tyrant who added a day to their birth month or a festival that pauses time. Make it feel like your characters live by it, whether they’re farmers, star-sorcerers, or wasteland rogues.

Before you go, I’ve got some thrilling news to share, and it’s gonna add some serious swagger to your gaming table! I’ve teamed up with the epic dice crafters at Only Crits as an affiliate, and I’m stoked to hook you up with a deal sweeter than elven mead. Pop over to their shop using my special link (

https://www.onlycrits.com/elvenmaidinn

) and punch in the code “ELF” at checkout to snag 10% off your entire cart. Who doesn’t need more dice in their life? Especially those sassy “Fuck Me” sets that turn every roll into a bold statement! When you shop through my link, I earn a 5% commission, which keeps the Elven Maid Inn’s fires burning and more homebrew content flowing your way.

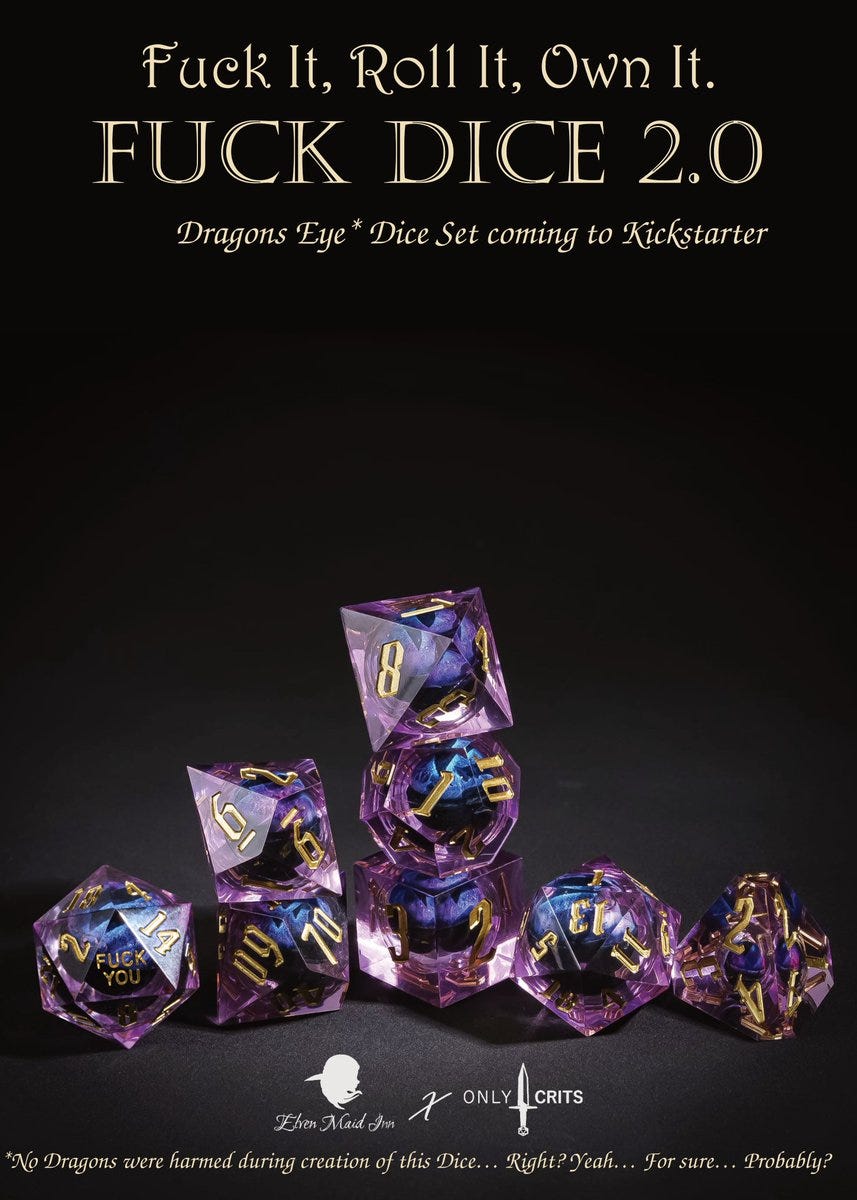

And for you dice dragons out there, here’s a hot tip: the “Fuck Dice 2.0” Kickstarter is crashing onto the scene on June 16, 2025! Brought to you by Only Crits, this sequel ramps up the legend with all the iconic designs from the first campaign, over 1,000 backers raised $97,930 CAD last time, plus 15 dazzling new sets, including the jaw-dropping Dragon Eye Dice. These purple-and-gold beauties swirl with attitude, transforming your Natural 1s into a “Fuck Me” and your Natural 20s into a “Fuck You” with epic flair. The first 150 backers get a free d20 of their choice, so don’t miss out! Check the Elven Maid Inn’s link (

https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/onlycrits/fuck-me-dice?ref=cv3l8g

) to pledge and roll like a true tavern hero. No dragons were harmed in the making (we hope, but they might’ve been a bit jealous!).

So, go forth, craft those calendars, and let your worlds shine! Keep rolling, keep creating, and let’s make some stories that echo through the ages.