The Fading Dark: How D&D Forgot to Fear the Darkness

First, my deepest apologies for the recent quiet on the blog. The past few weeks have tested me, body and mind, as I wrestle with challenges I’m working hard to overcome. Your patience means everything, and I’m committed to bringing you more stories, insights, and adventures soon. To those who’ve placed ads on the blog, thank you for your trust—I promise to honor every commitment we’ve made.

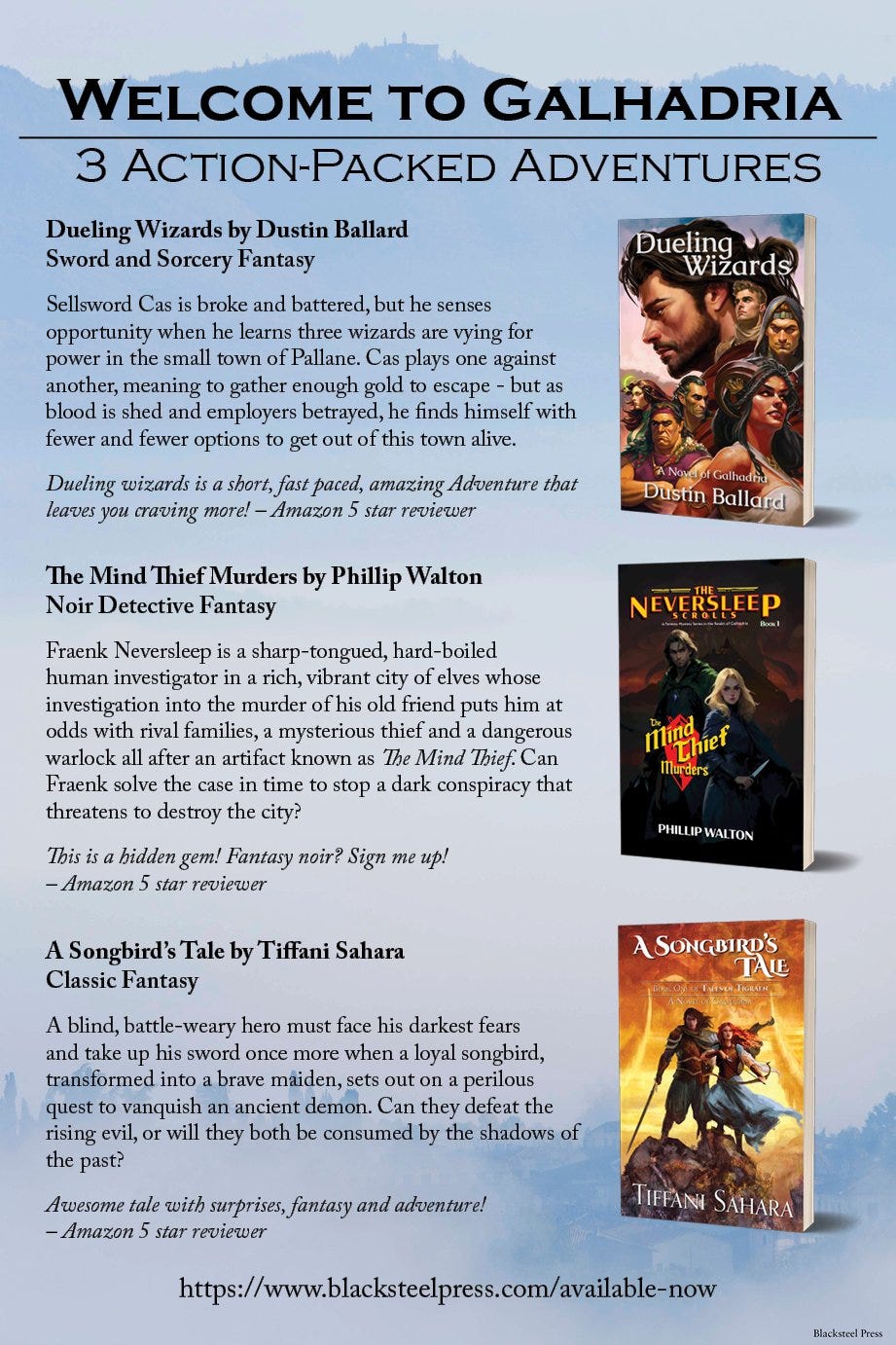

Today’s journey into the shadows is brought to you by Dustin Ballard, a brilliant fantasy writer and a true champion of creators. His passion for storytelling inspires us all, and I urge you to dive into his books and those of his talented associates. Check them out—you won’t be disappointed!

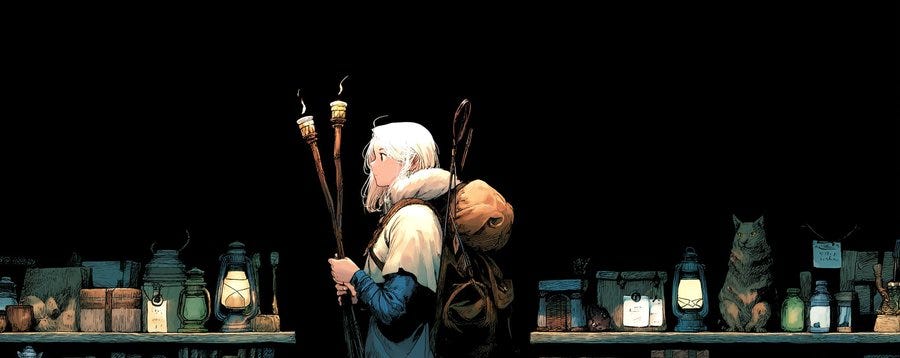

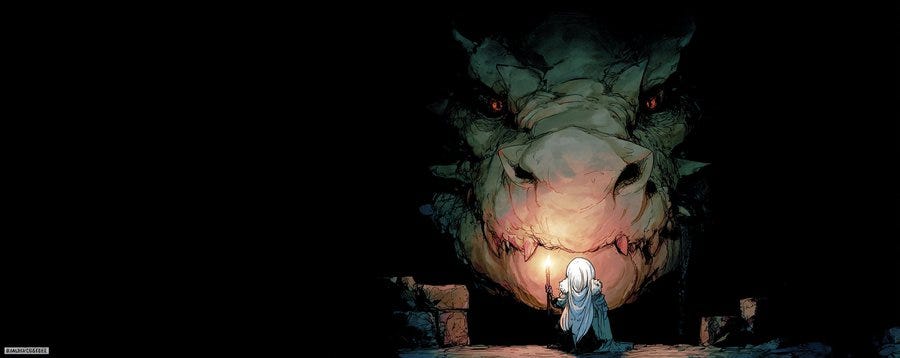

Now, let’s venture into the heart of Dungeons & Dragons. In its earliest days, darkness wasn’t just a setting—it was a force, a primal fear that shaped every step through torchlit tunnels. Somewhere along the way, modern D&D illuminated its dungeons, leaving that terror behind. In this article, we’ll explore why darkness mattered, how it faded, and why it’s time to bring it back. Grab your lanterns—let’s descend.

Darkness is one of humanity’s oldest fears. In the absence of light, the unknown thrives—monsters lurk, paths vanish, and the mind conjures horrors from shadows. In Dungeons & Dragons , a game built on imagination and peril, darkness was once a central mechanic, a force that shaped exploration and survival. Early editions treated it as a tangible threat, not just a backdrop. Yet, modern D&D has largely illuminated its dungeons, sidelining the fear of the dark in favor of accessibility and streamlined play. This article explores the role of darkness in D&D’s history, how it faded, why it matters, and how to bring it back.

Darkness in Early D&D: A Core Mechanic

In the earliest days of D&D, darkness wasn’t just a setting—it was a mechanic woven into the game’s fabric. The 1974 Original Dungeons & Dragons rules, often called the "White Box," emphasized resource management and survival. Dungeons were pitch-black labyrinths, and light sources were critical. The D&D booklets stated:

"In the underworld, some light source or an infravision spell must be used. Torches, lanterns, and magical weapons will provide light…" (Dungeons & Dragons Book III: The Underworld & Wilderness Adventures, p. 9).

Torches burned for a mere hour, lanterns required oil, and both could be extinguished by wind, water, or monsters. Without light, players were effectively blind, unable to navigate or fight effectively. This made dungeon exploration tense; every turn spent in the dark risked disaster. The Basic Set (1977, Holmes edition) reinforced this:

"A torch or lantern will burn for only a limited amount of time, and the party must have an adequate supply or face being stranded in the dark" (Dungeons & Dragons Basic Set, p. 22).

Darkness amplified the unknown. A simple encounter with goblins became terrifying when you couldn’t see beyond 30 feet. The Advanced Dungeons & Dragons (AD&D) Dungeon Master’s Guide (1979) doubled down, detailing light radii—torches cast 40 feet of illumination, lanterns 60—and warning DMs to track time meticulously (p. 97). Infravision, a precursor to darkvision, was limited to heat-based sight and useless for reading maps or spotting traps. Darkness forced players to plan, conserve resources, and fear what lay beyond their flickering flames.

This approach mirrored the game’s roots in pulp fantasy and horror. Inspirations like Robert E. Howard’s Conan stories or H.P. Lovecraft’s cosmic dread often placed heroes in claustrophobic, shadowy settings. Darkness wasn’t just a lack of light; it was a psychological force, a reminder of mortality. As Gary Gygax wrote in the AD&D Player’s Handbook (1978):

"The Dungeon Master will have considerable leeway in deciding what happens to characters who are in the dark…" (p. 102).

The Gradual Illumination: When Dungeons Got Brighter

The shift away from darkness began subtly but accelerated across editions. By tracing D&D’s evolution, we can pinpoint when and why dungeons became lighter.

AD&D 2nd Edition (1989): Streamlining Begins

AD&D 2nd Edition retained much of 1st Edition’s grit but introduced a more narrative focus. While darkness rules persisted—torches still burned for an hour (Dungeon Master’s Guide, 1989, p. 69)—the game’s tone shifted toward heroic fantasy. Modules like Dragonlance emphasized epic quests over gritty survival, and DMs were encouraged to prioritize story over strict resource tracking. Infravision became more common among races, reducing reliance on light sources. The fear of darkness started to wane as players expected more agency and less punishment.

D&D 3rd Edition (2000): The Rise of Darkvision

The release of D&D 3rd Edition marked a turning point. The Player’s Handbook (2000) introduced "darkvision," replacing infravision with a more powerful ability:

"Darkvision is the extraordinary ability to see with no light source at all, out to a range specified for the creature" (Player’s Handbook, p. 294).

Dwarves, gnomes, and half-orcs gained 60-foot darkvision, and elves had low-light vision. This made entire parties less dependent on torches. The Dungeon Master’s Guide (2000) still advised tracking light (p. 93), but the game’s focus on tactical combat and character optimization overshadowed survival mechanics. Dungeons were designed with encounter balance in mind, not atmospheric dread. The proliferation of magic items—like everburning torches—further trivialized darkness.

D&D 4th Edition (2008): Darkness as an Afterthought

4th Edition prioritized accessibility and cinematic combat, sidelining environmental hazards. The Player’s Handbook (2008) expanded darkvision to more races and simplified light rules:

"A torch or lantern provides bright light in a 10-square radius" (Player’s Handbook, p. 262).

However, the game assumed players could see unless explicitly stated otherwise. Dungeons were often described as dimly lit or magically illuminated, reducing the need for light sources. The focus on "points of light" settings—safe havens in a dangerous world—ironically made darkness less threatening. Players expected to be the light, not fear the dark.

D&D 5th Edition (2014): The Modern Standard

5th Edition cemented the trend. The Player’s Handbook (2014) grants darkvision to nearly half the core races, including elves, dwarves, gnomes, half-orcs, tieflings, and more (p. 20-43). Darkvision now extends to 60 feet (or 120 for some subclasses), allowing characters to see in total darkness without penalty. Light sources are an afterthought:

"A torch burns for 1 hour, providing bright light in a 20-foot radius and dim light for an additional 20 feet" (Player’s Handbook, p. 153).

The Dungeon Master’s Guide (2014) barely mentions darkness, offering vague advice:

"Track light sources if you want to add realism" (p. 105).

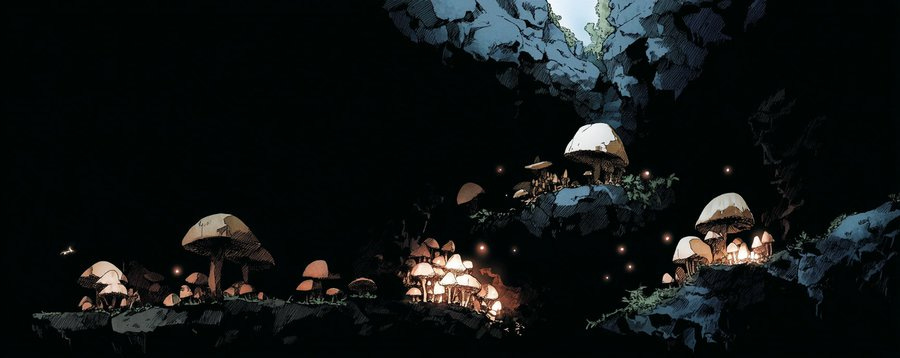

Most published adventures, like Curse of Strahd or Tomb of Annihilation, assume parties have darkvision or magical light (light cantrip is widely available). Dungeons are often described as faintly lit by glowing fungi or ancient runes, removing the need for torches. The game’s streamlined rules prioritize fun over fear, and darkness feels like a minor inconvenience rather than a threat.

Why Did Darkness Fade?

Several factors explain this shift:

Accessibility and Player Expectations: Modern D&D caters to broader audiences. Tracking torches and oil feels tedious to players accustomed to video games where visibility is assumed. Darkvision simplifies gameplay, letting players focus on combat and roleplay.

Design Philosophy: Since 3rd Edition, D&D has emphasized character power and heroic fantasy. Darkness, with its inherent limitations, clashes with the idea of unstoppable adventurers. Designers leaned toward mechanics that empower rather than restrict.

Cultural Shifts: Early D&D drew from horror and survival genres, where darkness symbolized danger. Modern fantasy, influenced by high-fantasy films and novels, treats light as a given—think Lord of the Rings, where glowing swords and elven grace banish shadows.

Mechanical Streamlining: Resource management fell out of favor as D&D evolved. Tracking ammunition, rations, and light sources was seen as bookkeeping, not storytelling. Darkvision and spells like light eliminated these logistics.

The Cost of Losing Darkness

The sidelining of darkness has consequences for D&D’s tone and immersion. Here’s why it matters:

1. Loss of Tension and Immersion

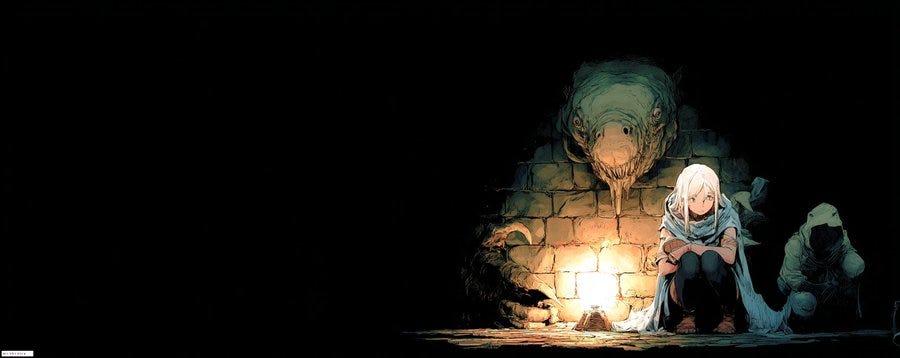

Darkness creates suspense. A party creeping through a dungeon, their torch casting flickering shadows, feels vulnerable. Every noise hints at danger. Modern D&D, with its ubiquitous darkvision, removes this. Players see threats coming, reducing the unknown’s power. As horror author Ramsey Campbell noted, “The essence of fear is uncertainty.” Without darkness, dungeons feel like well-lit arenas, not perilous unknowns.

2. Diminished Resource Management

Early D&D forced players to prioritize. A torch or lantern wasn’t just light—it was weight, cost, and vulnerability. Choosing between carrying extra oil or treasure added strategic depth. Modern D&D’s reliance on darkvision eliminates these choices, flattening exploration into a series of combat encounters.

3. Undermined Horror and Atmosphere

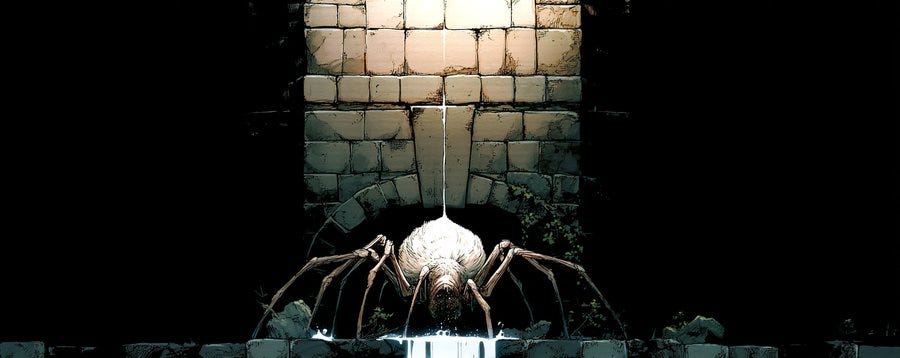

D&D draws from gothic and pulp traditions, where darkness amplifies dread. Strahd’s castle or the Underdark should feel oppressive, their shadows thick with menace. But if players see perfectly thanks to darkvision, the atmosphere suffers. A crypt bathed in monochrome clarity loses its mystery; a chasm’s depths feel mundane when every crack is visible. The Dungeon Master’s Guide (2014) hints at evoking mood through environment (p. 103), yet modern adventures rarely lean into darkness as a tool. Stripped of its power, the game’s horror roots—think Lovecraft’s lurking unknowns or Stoker’s claustrophobic castles—fade, leaving dungeons feeling more like tactical maps than haunting realms.

4. Weakened Monster Threat

Monsters lose their edge without darkness. A beholder lurking in shadows is terrifying; one spotted at 60 feet is just a target. The Monster Manual (2014) describes creatures like drow thriving in darkness (p. 128), but if players see as well as they do, the advantage vanishes.

5. Missed Narrative Opportunities

Darkness shapes stories. A party’s torch sputtering out during a chase, or a villain extinguishing lights before striking, creates drama. Modern D&D rarely uses these moments, as designers assume players are immune to darkness.

The Case for Bringing Darkness Back

Restoring darkness doesn’t mean reverting to 1974’s punishing rules—it means recapturing its emotional and mechanical weight. Here’s why and how to do it:

Why It Matters:

Restores Fear and Wonder: Darkness reintroduces the unknown, making dungeons feel alive and dangerous. It reminds players their characters aren’t invincible.

Enhances Exploration: Light management encourages planning and creativity. Players must decide when to risk light, hide, or flee, deepening decision-making.

Amplifies Roleplay: Fear of the dark reveals character. Does the paladin stand firm? Does the rogue panic? These moments define personalities.

Supports Modern Design: Darkness can coexist with 5e’s accessibility. It doesn’t need to be punitive—just impactful enough to matter.

How to Bring It Back:

Rethink Darkvision:

Remove completely or at least Limit its range (e.g., 30 feet) or make it monochrome, reducing clarity.

Require concentration or a resource cost to use it.

Example: In Pathfinder 2e, darkvision doesn’t negate all penalties—it mitigates them, keeping light relevant (Core Rulebook, p. 465).

Enforce Light Mechanics:

Track torch and lantern duration in key moments (e.g., chases, timed missions).

Make light sources vulnerable—wind, water, or enemy spells can extinguish them.

Example: In Curse of Strahd, describe Barovia’s fog dimming torches, forcing reliance on dwindling supplies.

Design Dark Dungeons:

Avoid default illumination (glowing mushrooms, runes). Let dungeons be pitch-black unless players bring light.

Use dynamic lighting—shadows shift as enemies move, hinting at threats.

Example: Tomb of Annihilation’s jungle could block ambient light, making torches essential.

Integrate Darkness Narratively:

Make darkness a villain’s tool—cultists snuff out lights before ambushing.

Tie it to lore: an ancient curse cloaks the dungeon in unnatural dark.

Example: In Ravenloft (1983), Strahd’s castle used darkness to disorient players (I6: Ravenloft, p. 12).

Balance Accessibility:

Offer alternatives like light spells or affordable lanterns, but limit their duration or reliability.

Let players overcome darkness creatively (e.g., bioluminescent allies, glowing weapons).

Example: In Old-School Essentials, a retroclone of Basic/Expert D&D, light rules are simple but strict, keeping tension without overwhelming bookkeeping (Old-School Essentials, p. 110).

Addressing Counterarguments

Some argue darkness is outdated or unfun. Here’s why those concerns don’t hold:

“It’s too punishing.”

Modern players aren’t fragile—5e’s death saves and healing options make survival easier than in 1974. Darkness adds challenge, not cruelty.

“It slows the game.”

Simple rules (e.g., torches last 10 rounds) minimize bookkeeping. DMs can hand-wave tracking outside critical moments.

“Players hate limitations.”

Constraints breed creativity. Players will invent solutions—glowing swords, allied fireflies—if given the chance.

“Darkvision is iconic.”

It can stay, but toned down. Make it a tool, not a cure-all.

Darkness defined D&D’s early soul, turning dungeons into realms of fear and wonder. Over decades, it faded—first through design shifts in AD&D 2e, then darkvision’s rise in 3e, and finally 5e’s streamlined heroism. This loss dulled the game’s edge, robbing players of tension, strategy, and awe. Yet, darkness can return without breaking modern D&D. By tweaking darkvision, enforcing light’s limits, and designing shadowy dungeons, DMs can restore what made the game iconic.

The dark isn’t just a mechanic—it’s a story. It’s the moment a torch gutters, and the party holds its breath. It’s the shadow that moves before the monster appears. It’s the fear that makes triumph sweeter. D&D thrives on imagination, and nothing sparks it like the unknown. Let’s turn out the lights and see what waits.